A Rymer Gallery Exhibition - originally published in Nashville Arts Magazine - http://nashvillearts.com

Logan Halsey • "Anima" is an evocative title. The living soul, the grammatical root of animal, Jung's unconscious feminine aspects of a male. Could you tell me how you envision these meanings and energies interacting and intertwining with each other in your collection?

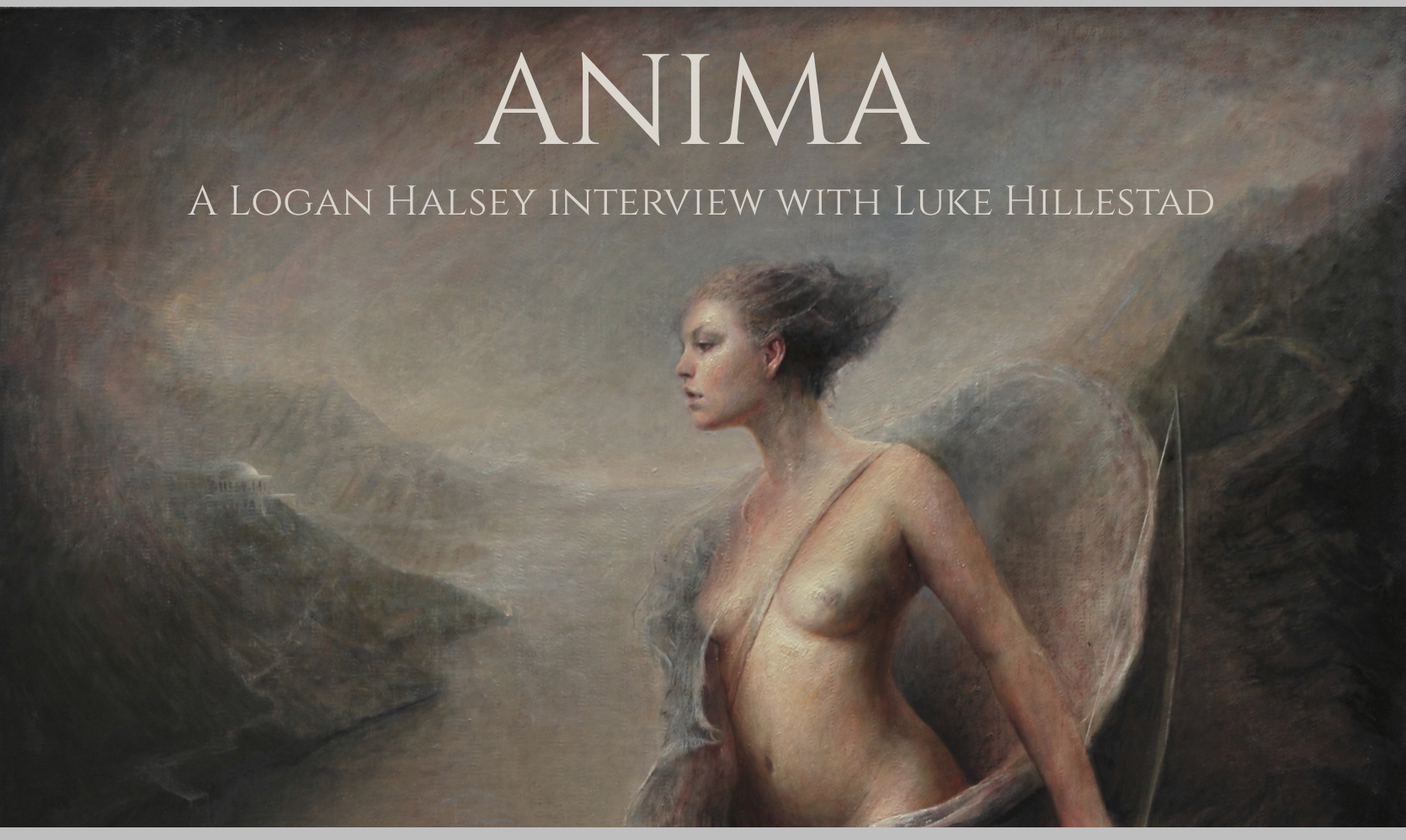

Luke Hillestad • I like that Anima can mean “breath”. Old philosophers saw the inhale/exhale cycle as fundamental for a certain kind of life. I think of seeing a sleeping dog, the gentle rising and falling stomach. I feel a respect, maybe love, for the dog - even just for it’s breathing. My primary painterly concern is this… I want to animate the surface of my canvas. I want to paint characters that breathe and narratives that are living.

Perhaps I won’t talk too much about Jung’s Anima idea, but I will say that I frequently look to these writings. For me, now, it is wonderful for this topic to stay misty and pictorial.

Victor is a picture of a character like Odysseus, who set out to sea on the day this dog was born. After 20 years of war, distraction, and tragedy he returns, and the dog is the first to greet him. Later that day the dog dies. They were only together for two of their days, but they share this moment. I break down at this sentimentality - however coincidental. There is something deep for me here. For his family, I imagine, the dog came to fill a loyalty void left by their absent father and husband. For Odysseus the dog probably represented all he hadn’t experienced with his family. The dog - it lived a full life with epic bookends.

“I would be happy to make copies all day, like the Romans did.”

Logan • Your last article in Nashville Arts Magazine, and much of the literature surrounding you, emphasizes the influence of your apprenticeship with Odd Nerdrum and the tradition of Apelles of Cos on your work. Your work remains distinct from your influences, however; how is your individual voice emerging in this collection?

Luke • I am quite serious when I say that if my work is distinct from Nerdrum, Rembrandt, or Titian it is accidental and likely for my lack of skill. And here I am talking about my preferences. I am often dissatisfied the result in my own work. Titian’s paintings improved after studying Apelles, and we wouldn’t know Rembrandt as a genius if he hadn’t discovered Titian. These masters displayed compounding qualities, and I see in their late works my highest goals. They are all so similar - golden and vibrating. If it weren’t for my rigid ego wanting be known for a masterpiece of my own - I would be happy to make copies all day, like the Romans did.

I will find myself thinking, “wouldn’t it have been great if Caravaggio lived longer!? If he had adopted Titian’s brushstroke?” If his dynamic scale was filled with a more tender flesh and his genius for drama was fuzed with the sensitivity of older age - well this could have been better than anything I’ve ever seen!! Then I pause. These are my preferences, my values, if you like, my individuality. What if I work towards making my imagined late-Caravaggio? It could be mine!

Logan • Before becoming a painter, you had a background in classical guitar, music composition, and land surveying. In what ways have these disciplines informed your approach to painting?

Luke • Studying music composition gave me a sense for proportion and harmony - also, in a way, narrative - or let’s say “poetics”. Performance taught me about daily practice and on-the-spot delivery. My school’s music program was much more classical than it’s Art program. I think my painting was better for studying music there. I talk with my old bandmate, Brett Bullion who now produces and engineers music, about the similarities in our crafts. About atmosphere, volume, depth, sharp and soft edges, warm and cool tones; we are learning side by side to manage these factors. We are discovering how to make our pieces gripping.

I also worked for 5 years as a land surveyor. Here I developed a knack for precision, geometry, and a taste for the wilderness - but more, I learned good work requires time in the trenches. It was hard for me and I developed a blue collar sensibility. I am still thrilled each day I get to paint.

Logan • In a contemporary art world that is characterized by abstraction and a fascination with individualism and all things new, you have chosen to return to traditional style and values. For yourself and for the artistic community, what is gained by returning to these narrative and figurative Renaissance values?

Luke • The Art system’s demand for originality was an undesirable prison for me. So I didn’t choose it. It is relaxing to ignore this Art value and openly choose my preferences, no matter how passé, nostalgic, and kitsch they are. Yes my work is traditional, but just one of countless traditions. The one I chose runs through the Greek Classical and it’s “rebirth” in the Baroque Renaissance. Wonderful painters also found success in this tradition 200 years later in the 1800’s.

If there is something more to be gained for us in this, other than the joy of freely choosing one’s craft, I would say it is empathy. The deliberate process of painting a face with dignity gives us practice in compassion. Time spent in front of an earnest portrait can leave the viewer a little more open, a bit more trusting.

“There is a disdain for the body. If this is modernism, I prefer the alternative classical mentality - which can now be called Kitsch.”

Logan • Modernism is often associated with a deep sense of cynicism. Your work eschews Modernism's irony, formal experimentation, and abstraction in favor of narrative, tradition, and figurativism. Do you feel that your work fights cynicism or other pitfalls of Modernism? How?

Luke • I am fond of the Cynics from 300 BC - they knew the best life was to include struggle. So these folks stepped outside the cities wanting a fresh perspective. Like when we travel out to the country and the night sky becomes so beautiful.

Irony is not attractive to me - the kind that purposefully ignores a subject; it puts a cool distance between us and pain. I don’t begrudge those who’s lives have been so difficult that irony feels like protection. Still my values are with those who have the courage to portray that open trusting face and to live sentimentally.

Earnest figurative painting feels quite dangerous for many people - it is against the law in some places. There is a disdain for the body. If this is modernism, I prefer the alternative classical mentality - which can now be called Kitsch.

Logan • I have heard you say in an interview that you wish to make art that seems as though it could have been made at any time. Your art is also deeply concerned with narrative. This suggests that you envision an overarching metanarrative about people, art, and narrative itself. What narratives does your work connect modern subjects to? How do you accomplish this?

Luke • I would say that my favorite paintings look as though they could have been made in any time, and definitely they would also be chalk full of narrative. You ask if I am therefore looking for a meta-narrative. No, I don’t think so. At least I am not interested in the metaphysics of “human direction”. This was Hegel’s mission and I find it incredibly constraining, if not dangerous. By timeless narratives I mean the stories that repeat regardless of geopolitics. These are archetypes: family, ritual, journey… the topics we each have versions of - the ones we recognize. When we see these themes shown poetically, we can have some beauty.

Logan • Your forebear Apelles, claimed by many sources to be the greatest painter of his time, is fascinating in that his own work does not survive (among many other reasons). Were it not for historical descriptions, recreations, and descendants of his work, his art could be considered “dead” in a sense. How is your sense of duty to this artist affected by this?

Luke • Some work dies after time because it was codependent with it’s own time. It is a sort of imminent death that comes to those following the fashion. I think Apelles’ work was different - it was murdered. The iconoclasts hated it and literally destroyed it. The ancient paintings that have survived, from places such as Pompeii, were described as quite weak compared to the paintings of Apelles. Imagine the beauty! It is not so much a duty I feel to Apelles, but a kinship I feel with him. Here again I get to imagine something fantastic he might have created - then make it myself - and it somehow becomes my own. My duty then, if I am successful, would be to give his storytellers credit for being my muse.

Logan • Visually, much of your work is characterized by thick, oppressive darkness which crawls all the way into the corners and threatens to overtake your subjects. And yet, your whites emerge triumphant and pure from this darkness (the lighthouse in Flight is a powerful example). What does this represent in the larger narrative of your work?

Luke • I suppose I find comfort in the darkness. Brightly lit cities make me anxious. I like candles, I like a lonely street lamp, I like a distant lighthouse. The daylight is rare and valuable. I need to work hard while the sun is up. It is at night that I will have most of my ideas for compositions.

“I am reminded of my frailty by my chest scar, my daily need for medication, and the ticking I hear when my heart pounds nervously. ”

Logan • Flight features a man with what appears to be a scar upon his chest. How have your past heart complications influenced your art and your outlook?

Luke • I had a few heart surgeries as a child and one of my valves was replaced with metal. I am reminded of my frailty by my chest scar, my daily need for medication, and the ticking I hear when my heart pounds nervously.

Flight is a picture of man who escaped a slave ship. He was part of the boat machine - one of the many rowers. So the ship crashed and he found an axe. He is about to join that stag in the wild. I got the idea from the late scene in “Cool hand Luke”. I still worry for this escapee though, seeing as Luke ended up trapped in the church with Dragline.

Logan • Unlike Grotto, for instance, in which the human subject seems to mirror the animal subject on many levels, Lazy Pirate is the only piece in the collection (that I have been shown, at least), which exclusively features an animal with no human counterpart. Given that he's stolen a pocket watch, is this perhaps a comment on the man in animal, rather than the other way around?

Luke • I like looking to animals for hints about how to live well. It is why I made the Lazy Pirate. This raccoon has stored some treasures. It doesn’t care about the time shown on the pocket watch - just the shiny metal. I like that.

Artemis portrays the hunter goddess. A determined maiden bound only to the partnership with her hound. She is a focused visionary, the dog is cautious and ardently loyal. They make a good pair.

The picture Grotto is an image about returning home after a catastrophe - the ritual of forgiveness. Here a woman, sure-footed but wary, emerges from a dark cave towards us. Her forward-leaning posture and wide eyes suggest a willingness; at the same time she restrains a wild bobcat at her heels - the primal urge to fight or flee. Around her are the overgrown Stone Arch ruins, perhaps remnants of an apocalyptic event. Green life springs from the cracks of man-made structures and a persistent trickle of life-giving water.

So with Anima I can pick the traits I admire from among the breathers - be they characteristically human or animal.